I guest edited Blake Butler’s Lamination Colony and the issue looks amazing. Blake asked me what I wanted it to look like and then he made it look like that. It’s all different-colored boxes that you have to scroll over until a name pops up and then you click on that some-colored box and there is something for you to love there.

There are 100 boxes and 38 writers and over 60 pieces. There is Kim Chinquee, Adam Robinson, Ben Mirov, DS White, Matthew Salesses, Blaster Al Ackerman, M.T. Fallon, Adam Good, Stephanie Barber, J.A. Tyler, Catherine Moran, Cooper Renner, Luca Dipierro, Amanda Raczkowski, Rupert Wondolowski, Whitney Woolf, Lauren Becker, Michael Bible, Robert Swartwood, Darcelle Bleau, Robert Bradley, Jamie Gaughran-Perez, Aimee Lynn-Hirschowitz, Shane Jones, Conor Madigan, Krammer Abrahams, Shatera Davenport, Jordan Sanderson, Stacie Leatherman, Josh Maday, Joseph Young, Jason Jones, Gena Mohwish, Jen Michalski, Aby Kaupang, Jac Jemc, Karen Lillis, and Justin Sirois.

Tuesday, 31 March 2009

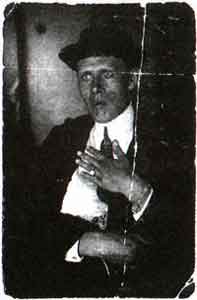

The Absurd in Prose Fiction - Part III: Daniil Kharms

We now return to Daniil Kharms (1905-1942): a non-person for much of the Stalin-Khrushchev period of Soviet Russia. The first selection of Kharms's work in Russia came only in 1988, amid glasnost, while the first collection in English – Russia’s Lost Literature of the Absurd – appeared in 1971. Recently, there has been a relative Kharms glut, beyond the reprinting of my selection of his work, Incidences. Collections have been published by Eugene Ostashevsky (OBERIU: An Anthology of Russian Absurdism) and Matvei Yankelevich (Today I Wrote Nothing). More recently, Kharmsian ballets, operas (notably the “music dramas” of Haflidi Hallgrimsson; plus Simon Callow’s reading of “Mini-Stories” to Hallgrimsson’s music), theatricals and so on, whether in Russia or the West, have become almost commonplace – at least within certain niche circles. There has even been talk of a BBC documentary. In the present age of postmodernist fragmentation, Kharms’s time has surely come.

We now return to Daniil Kharms (1905-1942): a non-person for much of the Stalin-Khrushchev period of Soviet Russia. The first selection of Kharms's work in Russia came only in 1988, amid glasnost, while the first collection in English – Russia’s Lost Literature of the Absurd – appeared in 1971. Recently, there has been a relative Kharms glut, beyond the reprinting of my selection of his work, Incidences. Collections have been published by Eugene Ostashevsky (OBERIU: An Anthology of Russian Absurdism) and Matvei Yankelevich (Today I Wrote Nothing). More recently, Kharmsian ballets, operas (notably the “music dramas” of Haflidi Hallgrimsson; plus Simon Callow’s reading of “Mini-Stories” to Hallgrimsson’s music), theatricals and so on, whether in Russia or the West, have become almost commonplace – at least within certain niche circles. There has even been talk of a BBC documentary. In the present age of postmodernist fragmentation, Kharms’s time has surely come.If Kharms seems different from previous absurdist models, or somehow more startling, this may be explicable through his constant adoption of a poetics of extremism. Take, for example, his brevity: not for nothing did he note in his diary: “garrulity is the mother of mediocrity”. If certain “stories” seem microtexts of concise inconsequentiality, others incommode the printer even less: consider the following “complete” story:

An old man was scratching his head with both hands. In places where he couldn’t reach with both hands, he scratched himself with one, but very, very, fast. And while he was doing it he blinked rapidly.Another “extreme” feature is Kharms’s uncompromising quest for the means to undermine his own writings, or to facilitate their self-destruction. He turns a surgical glance on the extraordinary world of Stalin’s Russia and on representation, past and present, in storytelling and other artistic forms. He operates, typically, against a precise Leningrad background, reflecting aspects of Soviet life and literary forms, passing sardonic and despairing comment on the period in which he lived. He also ventures, ludicrously, into historical areas, parodying the ways in which respected worthies (Pushkin, Gogol and Ivan Susanin) were glorified in print. Yet Kharms’s miniatures can seem strangely anticipatory of more modern trends, reflecting almost a politically correct America, or London’s cardboard city; one extract, “On an Approach to Immortality”, would surely fascinate Milan Kundera.

The most striking feature, for many, is the recurrence of Kharms’s strange and disturbing obsessions: with falling, accidents, chance, sudden death, victimization and apparently mindless violence. Frequently there appears little or no difference between his avowedly fictional works and his other writings. In his notebooks can be found such passages as:

I don’t like children, old men, old women, and the reasonable middle aged. To poison children, that would be harsh. But, hell, something needs to be done with them!...How far into the cheek the tongue may go is far from clear: the degree of narratorial identification remains problematic. The better known Kharmsian obsessions, too (such as falling), carry over into his notebooks and diaries:

I respect only young, robust and splendiferous women. The remaining representatives of the human race I regard suspiciously. Old women who are repositories of reasonable ideas ought to be lassoed...

Which is the more agreeable sight: an old woman clad in just a shift, or a young man completely naked? And which, in that state, is the less permissible in public?...

What's so great about flowers? You get a significantly better smell from between women’s legs. Both are pure nature, so no one dare be outraged at my words.

On falling into filth, there is only one thing for a man to do: just fall, without looking round. The important thing is just to do this with style and energy.The implications can seem particularly sinister, as in this note from 1940, which could equally be a sketch for a story, or even, as we have seen, a “mini-story” in itself:

One man was pursuing another when the latter, who was running away, in his turn, pursued a third man who, not sensing the chase behind him, was simply walking at a brisk pace along the pavement.Other entries rather more predictably affirm what might be supposed to be his philosophy:

I am interested only in ‘nonsense’; only in that which makes no practical sense. I am interested in life only in its absurd manifestation.This last, apparently frivolous, remark was written in 1937, at the height of Stalin's purges.

All this may be approached through the propositions of the absurd outlined above, or indeed by reference to the nature of the surrounding reality: in times of extremity, it is the times themselves which may seem more absurd than any artistic invention. For that matter, Kharmsian “incidents” (and “incidences”, “happenings” or “cases” – all possible translations of sluchai) have their ancestry in a multitude of genres and models: fable, parable, fairytale, children’s story, philosophical or dramatic dialogue, comic monologue, carnival, cartoon and silent movie – even the video-nasty. All seem present somewhere in Kharms, in compressed form and devoid of explanation, context and other standard trappings. Kharms, indeed, seems to serve up, transform or abort the bare bones of the sub-plots, plot segments and timeless authorial devices of world literature, from the narratives of antiquity to classic European fiction and the wordplay, plot-play and metafictions of our postmodern era. Kharms offers a skeletal terseness, in opposition to the comprehensive vacuousness of many more conventional literary forms.

As well as translating selections from the writings of Daniil Kharms (see above) and Mayakovsky’s My Discovery of America (Hesperus, 2005), Neil Cornwell is author of The Absurd in Literature (Manchester UP, 2006) and editor of Daniil Kharms and the Poetics of the Absurd (Macmillan, 1991). He is also Russian editor for the online Literary Encyclopedia. This article is the last of a three-part series.

Monday, 30 March 2009

John Updike’s The Witches of Eastwick – a fast-track process

It is with great sadness that I announce to the world I have given up reading Updike’s The Witches of Eastwick on page 10. I have just seen AA’s prophetic comment on my previous blog entry, which says: “Better go straight to The Plague – or any other book by Camus, for that matter – skipping The Witches.” Here’s my verdict on the book:

Did I like the book?

It ain’t my cup of tea. Not badly written, but baroque and overwritten to the point of paroxism. Too much fluff and – I can’t figure out what the heck is happening. I read the first ten pages three times, during three separate sessions. I give up.

What did I like most?

Er, the editing and the production, for once. . .

What didn’t work for me?

Just as for Sinclair Lewis, the prose seems to grow in a sort of tumorous way rather than flow naturally.

Would I publish it?

No. I loved the man when he was alive, and now I feel slightly guilty because I don’t like his work now that he’s gone. I am sorry, but even if many consider him one of the finest writers in the great American tradition, this book – for me – reads like the ichthyological parts of Moby Dick.

What if it came as an unsolicited manuscript?

I would pass.

Did it sustain my interest throughout?

Giving up on page 10 is not a good sign.

The best bit in the book?

I read too little to find one.

The best scene in the book?

Ditto.

Comments on the package, editing, typesetting?

After the nasty comments I have made in the past about other Penguin Classics titles, I must admit that this book, both for editorial care and quality of typography, package etc. is refreshingly good. I think the new Penguin Classics are miles better than the old ones in terms of quality. It’s a good sign.

My final verdict?

I’ll probably pick up another Updike book some time – possibly one from the celebrated Rabbit trilogy. But I am in no particular rush.

The next book I’m going to try will either be a Ionesco play or a Céline novel. More soon.

AG

Did I like the book?

It ain’t my cup of tea. Not badly written, but baroque and overwritten to the point of paroxism. Too much fluff and – I can’t figure out what the heck is happening. I read the first ten pages three times, during three separate sessions. I give up.

What did I like most?

Er, the editing and the production, for once. . .

What didn’t work for me?

Just as for Sinclair Lewis, the prose seems to grow in a sort of tumorous way rather than flow naturally.

Would I publish it?

No. I loved the man when he was alive, and now I feel slightly guilty because I don’t like his work now that he’s gone. I am sorry, but even if many consider him one of the finest writers in the great American tradition, this book – for me – reads like the ichthyological parts of Moby Dick.

What if it came as an unsolicited manuscript?

I would pass.

Did it sustain my interest throughout?

Giving up on page 10 is not a good sign.

The best bit in the book?

I read too little to find one.

The best scene in the book?

Ditto.

Comments on the package, editing, typesetting?

After the nasty comments I have made in the past about other Penguin Classics titles, I must admit that this book, both for editorial care and quality of typography, package etc. is refreshingly good. I think the new Penguin Classics are miles better than the old ones in terms of quality. It’s a good sign.

My final verdict?

I’ll probably pick up another Updike book some time – possibly one from the celebrated Rabbit trilogy. But I am in no particular rush.

The next book I’m going to try will either be a Ionesco play or a Céline novel. More soon.

AG

Labels:

Penguin Classics,

Updike,

Witches of Eastwick

Saturday, 28 March 2009

The Outsider by Albert Camus – the jury is in

I remember reading Camus’s Caligula a few years ago and being very impressed. I have now decided to try one of his celebrated short novels and see if it lived up to its reputation.

Did I like the book?

Yes, I think it’s a masterly work. It gets the reader straight into the story – great characterization, great scenes. Oddly funny at times.

What did I like most?

The unpretentiousness of the style, and the ease in which the existentialist themes are weaved into the storyline. The narrator’s voice, and consequently the story, is very believable.

What didn’t work for me?

The translation is generally good, but there are quite a few oddities – mostly concerning the choice of words. It’s a shame I don’t have the French text to hand, as I’d have liked to check the translation against the original. I think I spotted a handful of mistakes.

Would I publish it?

Without a doubt. If there’s a publisher in UK who could do a better job than Penguin, that would be – ahem – us: it would just fit nicely with the rest of our French classics list (Céline, Artaud, Ionesco, Duras, Robbe-Grillet etc.). I hope I can hang in there until it comes out of copyright on 1st January 2031. I’ll make a note on my diary.

What if it came as an unsolicited manuscript?

I would call an extraordinary publishing meeting and start getting printers’ quotes.

Did it sustain my interest throughout?

Yes, from beginning to end. Everything is in the balance to the very last paragraph.

The best bit in the book?

Probably towards the end, when the narrator is in his cell and as the priest is trying to make him turn to religious thoughts he says: “I went up to him and made one last attempt to explain to him that I didn’t have much time left. I didn’t want to waste it on God.” How can you beat that last sentence?

The best scene in the book?

There are many. The funeral, the killing, the process. But what I liked most is how Camus managed to bring alive the characters in the book – Raymond and old dog-beating neighbour – with a few light touches and bits of dialogue.

Comments on the package, editing, typesetting?

Ora veniamo alle dolenti note. This Penguin Modern Classics edition – which appears to have been acquired by the Kew Library towards the end of 2002 – is falling apart. It was taken out for the first time on 3rd December 2002 and the librarian scribbled the following note on the 22nd November 2008: “Spine noted”. From this I gather that a Penguin Modern Classics spine is made to last around six years or twenty-two reads (I counted the date stamps). Perhaps some sort of obsolescence is built in it, as in my watch strap. The paper seems to suffer from jaundice, and it’s full of strange yellow and brown stains. I think the paper’s dying. I haven’t spotted any typos, but there’s lots of in-house decisions that are questionable (for example: “he’d talked to me about mother” – surely it should be “Mother”?), and missing or misplaced commas, missing hyphens etc. What I would call a lazy editorial job, in short – especially for a book which is only around 100 pages long.

My final verdict?

A great read, a classic. Lucky Penguin for having it in their list. I want to read more Camus soon. But the next book on my desk is Updike’s The Witches of Eastwick, so I’ll report on that one as and when.

AG

Did I like the book?

Yes, I think it’s a masterly work. It gets the reader straight into the story – great characterization, great scenes. Oddly funny at times.

What did I like most?

The unpretentiousness of the style, and the ease in which the existentialist themes are weaved into the storyline. The narrator’s voice, and consequently the story, is very believable.

What didn’t work for me?

The translation is generally good, but there are quite a few oddities – mostly concerning the choice of words. It’s a shame I don’t have the French text to hand, as I’d have liked to check the translation against the original. I think I spotted a handful of mistakes.

Would I publish it?

Without a doubt. If there’s a publisher in UK who could do a better job than Penguin, that would be – ahem – us: it would just fit nicely with the rest of our French classics list (Céline, Artaud, Ionesco, Duras, Robbe-Grillet etc.). I hope I can hang in there until it comes out of copyright on 1st January 2031. I’ll make a note on my diary.

What if it came as an unsolicited manuscript?

I would call an extraordinary publishing meeting and start getting printers’ quotes.

Did it sustain my interest throughout?

Yes, from beginning to end. Everything is in the balance to the very last paragraph.

The best bit in the book?

Probably towards the end, when the narrator is in his cell and as the priest is trying to make him turn to religious thoughts he says: “I went up to him and made one last attempt to explain to him that I didn’t have much time left. I didn’t want to waste it on God.” How can you beat that last sentence?

The best scene in the book?

There are many. The funeral, the killing, the process. But what I liked most is how Camus managed to bring alive the characters in the book – Raymond and old dog-beating neighbour – with a few light touches and bits of dialogue.

Comments on the package, editing, typesetting?

Ora veniamo alle dolenti note. This Penguin Modern Classics edition – which appears to have been acquired by the Kew Library towards the end of 2002 – is falling apart. It was taken out for the first time on 3rd December 2002 and the librarian scribbled the following note on the 22nd November 2008: “Spine noted”. From this I gather that a Penguin Modern Classics spine is made to last around six years or twenty-two reads (I counted the date stamps). Perhaps some sort of obsolescence is built in it, as in my watch strap. The paper seems to suffer from jaundice, and it’s full of strange yellow and brown stains. I think the paper’s dying. I haven’t spotted any typos, but there’s lots of in-house decisions that are questionable (for example: “he’d talked to me about mother” – surely it should be “Mother”?), and missing or misplaced commas, missing hyphens etc. What I would call a lazy editorial job, in short – especially for a book which is only around 100 pages long.

My final verdict?

A great read, a classic. Lucky Penguin for having it in their list. I want to read more Camus soon. But the next book on my desk is Updike’s The Witches of Eastwick, so I’ll report on that one as and when.

AG

Labels:

Caligula,

Camus,

Penguin Classics,

The Outsider,

The Plague

Friday, 27 March 2009

“Fair Play is Foul and Foul Play is Fair”

This is, in a nutshell, what is happening in British publishing today.

Yesterday I went to one of the loveliest parties in years, to celebrate Capuchin Classics’ first birthday. Capuchin Classics, for the few of you who don’t know, is a great independent run by Hugh Grant’s younger and posher brother, who is known to the publishing community by the name of Max Scott. Their motto is “Books to keep alive”.

The venue was the company’s headquarters in Notting Hill, next door to Lucian Freud, I am told. As I have reported in a previous blog, all the antiques and works of art scattered casually in every nook and cranny of the house are properly insured.

This party was great because I didn’t see many of the obnoxious faces you bump into at other parties, and because I met a few interesting people, including two of Capuchin’s crusading editors – Emma and Christopher. The latter surprised the audience at one point with what must go down in history as one of the most politely controversial speeches in publishing history. I have been allowed to report it verbatim, as it’s a kind of press release:

“Interestingly, it was John Milton who, way back when the book was still, literally, fairly novel, observed that 'Books are not absolutely dead things, but contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul whose progeny they are.'

That sense of a legacy, then, is ever-present in today’s publishing industry. Or at least it should be. Those houses publishing in this tradition are relatively few in number – a couple are here tonight. Their books are published in the same spirit – that, literally, of making public. The view is on the long-term sales, and reaching every possible outlet.

Last year a new imprint launched, protégé of Faber and Faber, no less, which seeks not so much to put books before a browsing, buying public as to snuffle up authors’ estates from across the cannon.

We see this as a force against that tradition of a legacy. Sure, it keeps the book in print, but in the narrow sense of the term. The majority on that particular list are simply put out 'print on demand'. (The POD formula being, of course: chap walks into shop, orders a copy of Lucky Jim, book gets printed). While there are concessions for living authors (in the form of a release clause should a rival publisher put in an offer), this model is in our view lazy publishing, and short-sighted at best.

Our book-buyer had to know that Lucky Jim existed in the first place. After all, the fundamental truth remains that you cannot ask for what you do not already know exists – a law that applies as much to bookshops as it does in the land of Google. It is not, then, truly making public.

‘Foul play’, I hear you cry – and you’d be right. For this surely marks a step away from what it is to publish, and what it means to keep books alive. To the agents among you I would urge caution before conceding an author’s works to what is admittedly a prestigious name, but one that arguably undermines what it means, properly, to publish.”

I will only add Amen to that.

And to conclude this blog, I will say that there were only a couple of crazy women at this party, and that for some reason David Birkett, Capuchin’s sales director, the only working-class person – apart from me – in the house, I believe, seems to be developing a dangerous aristocratic lilt to his Londoner’s accent. I am really starting to worry about him.

AG

Yesterday I went to one of the loveliest parties in years, to celebrate Capuchin Classics’ first birthday. Capuchin Classics, for the few of you who don’t know, is a great independent run by Hugh Grant’s younger and posher brother, who is known to the publishing community by the name of Max Scott. Their motto is “Books to keep alive”.

The venue was the company’s headquarters in Notting Hill, next door to Lucian Freud, I am told. As I have reported in a previous blog, all the antiques and works of art scattered casually in every nook and cranny of the house are properly insured.

This party was great because I didn’t see many of the obnoxious faces you bump into at other parties, and because I met a few interesting people, including two of Capuchin’s crusading editors – Emma and Christopher. The latter surprised the audience at one point with what must go down in history as one of the most politely controversial speeches in publishing history. I have been allowed to report it verbatim, as it’s a kind of press release:

“Interestingly, it was John Milton who, way back when the book was still, literally, fairly novel, observed that 'Books are not absolutely dead things, but contain a potency of life in them to be as active as that soul whose progeny they are.'

That sense of a legacy, then, is ever-present in today’s publishing industry. Or at least it should be. Those houses publishing in this tradition are relatively few in number – a couple are here tonight. Their books are published in the same spirit – that, literally, of making public. The view is on the long-term sales, and reaching every possible outlet.

Last year a new imprint launched, protégé of Faber and Faber, no less, which seeks not so much to put books before a browsing, buying public as to snuffle up authors’ estates from across the cannon.

We see this as a force against that tradition of a legacy. Sure, it keeps the book in print, but in the narrow sense of the term. The majority on that particular list are simply put out 'print on demand'. (The POD formula being, of course: chap walks into shop, orders a copy of Lucky Jim, book gets printed). While there are concessions for living authors (in the form of a release clause should a rival publisher put in an offer), this model is in our view lazy publishing, and short-sighted at best.

Our book-buyer had to know that Lucky Jim existed in the first place. After all, the fundamental truth remains that you cannot ask for what you do not already know exists – a law that applies as much to bookshops as it does in the land of Google. It is not, then, truly making public.

‘Foul play’, I hear you cry – and you’d be right. For this surely marks a step away from what it is to publish, and what it means to keep books alive. To the agents among you I would urge caution before conceding an author’s works to what is admittedly a prestigious name, but one that arguably undermines what it means, properly, to publish.”

I will only add Amen to that.

And to conclude this blog, I will say that there were only a couple of crazy women at this party, and that for some reason David Birkett, Capuchin’s sales director, the only working-class person – apart from me – in the house, I believe, seems to be developing a dangerous aristocratic lilt to his Londoner’s accent. I am really starting to worry about him.

AG

Thursday, 26 March 2009

Controlling the stage...

Prospect magazine has just published an interesting article about Samuel Beckett, and the various wranglings that have ensued since Calder first published Beckett's prose in the 1950s. That Mr Calder has been one of the most important British publishers of avant-garde literature over the last 60 years is well-known: he has published works by Henry Miller, William Burroughs, and - almost - Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita - see the article in The Bookseller, I Am Legend for a little background.

The article takes issue with the apparently vice-like grip of the Beckett estate on the ways in which Beckett's plays may be performed. I find it hard to argue with the Colin Murphy that it's perhaps a bad thing that theatre rights should extend to the point of being able to stop a play being shown if it deviates too much from the text; apart from putting off first-timers to Beckett (which a poor but faithful production will do anyway), what other disadvantages are there to allowing a director full reign over his plays? Such conservatism simply seems ill-fitting to radical works like Beckett's. Now if it was Nabokov, it would be a different matter... and even he relaxed considerably to allow Kubrick the freedom he needed to make a successful film of Lolita.

All works are open to various degrees of interpretation, and if a director decides on something ludicrous (such as setting Endgame on the moon) then his or her production will be judged accordingly by the theatre-goers. We've all seen or heard of tepid productions of Shakespeare variously done in drag or decked out in conveniently affordable military gear; rattled off in thirty seconds or stretched out for three or four hours; done 'topically' to deal with animal rights, hermaphroditism and/or globilization... but these don't seem to be a reflection on the Bard's work, rather on the directors'. The essence of a great work lies in its being so open to interpretation, otherwise the critics would lay down their pens after the last word has been said and simply go to bed.

The article takes issue with the apparently vice-like grip of the Beckett estate on the ways in which Beckett's plays may be performed. I find it hard to argue with the Colin Murphy that it's perhaps a bad thing that theatre rights should extend to the point of being able to stop a play being shown if it deviates too much from the text; apart from putting off first-timers to Beckett (which a poor but faithful production will do anyway), what other disadvantages are there to allowing a director full reign over his plays? Such conservatism simply seems ill-fitting to radical works like Beckett's. Now if it was Nabokov, it would be a different matter... and even he relaxed considerably to allow Kubrick the freedom he needed to make a successful film of Lolita.

All works are open to various degrees of interpretation, and if a director decides on something ludicrous (such as setting Endgame on the moon) then his or her production will be judged accordingly by the theatre-goers. We've all seen or heard of tepid productions of Shakespeare variously done in drag or decked out in conveniently affordable military gear; rattled off in thirty seconds or stretched out for three or four hours; done 'topically' to deal with animal rights, hermaphroditism and/or globilization... but these don't seem to be a reflection on the Bard's work, rather on the directors'. The essence of a great work lies in its being so open to interpretation, otherwise the critics would lay down their pens after the last word has been said and simply go to bed.

Labels:

Beckett,

John Calder,

Theatre

Wednesday, 25 March 2009

The Absurd in Prose Fiction - Part II: Absurdism in the West

The term “the absurd” is applied to literature in several ways. It describes a “school” of dramatic writing (though not all care to accept it as such), in the case of “Theatre of the Absurd”. It is also considered a prominent period style – observable, approximately, over the two middle quarters of the twentieth century (stretching roughly from the end of the First World War up until, say, the 1970s). Or it may be a category with philosophical (usually Existentialist) implications – in other words, a timeless quality, which may be seen pertaining here and there throughout literary history.

A major figure of the first half of the twentieth century was Franz Kafka. Most of his work was published only after his early death in 1924 and his reputation has burgeoned ever since, to the point that adaptations and imitations of his works abound (by, among others, Harold Pinter, Steven Berkoff and Alan Bennett), and “Kafkaesque” has become an everyday adjective. His novels The Trial and The Castle, along with shorter stories (notably Metamorphosis and In the Penal Colony) have established Kafka as the unsurpassed master-purveyor of endless streams of sinister bureaucracy and the creeping encroachments of indeterminate and hostile powers. “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect” (Metamorphosis) stands as one of the most startling opening sentences in world literature. Kafka may be classed as an absurdist par excellence – one whose creative career ended a quarter of a century before the Theatre of the Absurd, as it is now recognised, had begun.

A principal representative of both absurdist prose and Theatre of the Absurd (of which he is seen as one of the founding figures) is Samuel Beckett. A writer spanning Anglo-Irish and French literature in unique fashion, Beckett was resident in Paris from the 1930s, writing in English, then in French, and subsequently in both, translating his own works both ways. His early English prose writings, notably Murphy (1938) and Watt (begun 1941; published 1953), are, in part at least, examples of what might be called “Irish grotesque”. But Watt (written in wartime France) marks a turning point in Beckett’s prose – one indeed firmly towards the absurd. The emphasis here is placed greatly on Watt’s inner world, along with the introduction of a mysterious third world – that of the house and system of Mr Knott (in and under which the protagonist spends much of the novel’s “action”). After Watt, Beckett soon began writing his prose in French (“from a desire”, he said, “to impoverish myself still further”), as well as making another switch – into first-person narrative. First Love and the three other novellas of 1946 were written almost in anticipation of the so-called “trilogy” of novels – Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnamable. These were the works that established Beckett as an exponent of absurdist prose, retreating ever further into what have been called “skullscapes” (or “frescoes of the skull”, the term used by James Knowlson and John Pilling), alongside his rising theatrical prowess. Beckett’s next fiction, Texts for Nothing, confirms the progression towards constriction and the minimal – a self-styled “farrago of silence and words”, engaged in “panting towards the grand apnoea” of negativity. Of his subsequent prose, let’s mention just The Lost Ones, in which Beckett creates a horrific and entropic mini-universe, the enclosed space of a flattened cylinder, inhabited by 200 people engaged in a hopeless “quest” for an exit. The observation that “in this old abode all is not yet quite for the best” stands as one of absurdist literature’s great understatements.

Another Irishman making a significant contribution to absurd prose was Flann O’Brien (the novelistic pen name of Brian O’Nolan: 1911-1966). A famed Irish Times columnist, O'Brien wrote the novel The Poor Mouth (1941) in Irish, his first language, but is now mainly remembered for two remarkable experimental and absurdist novels: At Swim-Two Birds and The Third Policeman. The main feature of the former – its stylistic and generic variations apart – is the presence of a novel within the novel, and the takeover of the inner novel’s writing by its characters, who exact revenge upon their author. The Third Policeman, suppressed by its author during his lifetime (or, rather, just left lying about), is O’Brien’s masterpiece. Here complexity of form is equalled, or even excelled, by that of a content having a strongly disturbing effect on many readers (including reportedly O’Brien himself). The plot involves murder and a hellish and apparently circular afterlife, in which the narrator is tormented by absurd policemen in a supernatural zone called “The Parish”.

In America, two notable novels of the absurd are J.P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man (1955) and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (1961). Donleavy uses a mainly (all but infernal) Dublin setting of chaos and absurdity, largely created by the protagonist, Sebastian Dangerfield – the anglicized-hibernicized American antihero and mock-Christ figure. Catch-22 is dominated by a bureaucratic-military absurd, represented emblematically by the title, which is, of course, itself now more than a catch phrase. Set in the World War Two “theatre” of Italy, this novel was influential during the Vietnam War period, and takes on a renewed significance with the Gulf wars and the “War on Terrorism”.

As well as translating selections from the writings of Daniil Kharms (see above) and Mayakovsky’s My Discovery of America (Hesperus, 2005), Neil Cornwell is author of The Absurd in Literature (Manchester UP, 2006) and editor of Daniil Kharms and the Poetics of the Absurd (Macmillan, 1991). He is also Russian editor for the online Literary Encyclopedia. This article is the second of a three-part series.

A major figure of the first half of the twentieth century was Franz Kafka. Most of his work was published only after his early death in 1924 and his reputation has burgeoned ever since, to the point that adaptations and imitations of his works abound (by, among others, Harold Pinter, Steven Berkoff and Alan Bennett), and “Kafkaesque” has become an everyday adjective. His novels The Trial and The Castle, along with shorter stories (notably Metamorphosis and In the Penal Colony) have established Kafka as the unsurpassed master-purveyor of endless streams of sinister bureaucracy and the creeping encroachments of indeterminate and hostile powers. “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect” (Metamorphosis) stands as one of the most startling opening sentences in world literature. Kafka may be classed as an absurdist par excellence – one whose creative career ended a quarter of a century before the Theatre of the Absurd, as it is now recognised, had begun.

A principal representative of both absurdist prose and Theatre of the Absurd (of which he is seen as one of the founding figures) is Samuel Beckett. A writer spanning Anglo-Irish and French literature in unique fashion, Beckett was resident in Paris from the 1930s, writing in English, then in French, and subsequently in both, translating his own works both ways. His early English prose writings, notably Murphy (1938) and Watt (begun 1941; published 1953), are, in part at least, examples of what might be called “Irish grotesque”. But Watt (written in wartime France) marks a turning point in Beckett’s prose – one indeed firmly towards the absurd. The emphasis here is placed greatly on Watt’s inner world, along with the introduction of a mysterious third world – that of the house and system of Mr Knott (in and under which the protagonist spends much of the novel’s “action”). After Watt, Beckett soon began writing his prose in French (“from a desire”, he said, “to impoverish myself still further”), as well as making another switch – into first-person narrative. First Love and the three other novellas of 1946 were written almost in anticipation of the so-called “trilogy” of novels – Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnamable. These were the works that established Beckett as an exponent of absurdist prose, retreating ever further into what have been called “skullscapes” (or “frescoes of the skull”, the term used by James Knowlson and John Pilling), alongside his rising theatrical prowess. Beckett’s next fiction, Texts for Nothing, confirms the progression towards constriction and the minimal – a self-styled “farrago of silence and words”, engaged in “panting towards the grand apnoea” of negativity. Of his subsequent prose, let’s mention just The Lost Ones, in which Beckett creates a horrific and entropic mini-universe, the enclosed space of a flattened cylinder, inhabited by 200 people engaged in a hopeless “quest” for an exit. The observation that “in this old abode all is not yet quite for the best” stands as one of absurdist literature’s great understatements.

Another Irishman making a significant contribution to absurd prose was Flann O’Brien (the novelistic pen name of Brian O’Nolan: 1911-1966). A famed Irish Times columnist, O'Brien wrote the novel The Poor Mouth (1941) in Irish, his first language, but is now mainly remembered for two remarkable experimental and absurdist novels: At Swim-Two Birds and The Third Policeman. The main feature of the former – its stylistic and generic variations apart – is the presence of a novel within the novel, and the takeover of the inner novel’s writing by its characters, who exact revenge upon their author. The Third Policeman, suppressed by its author during his lifetime (or, rather, just left lying about), is O’Brien’s masterpiece. Here complexity of form is equalled, or even excelled, by that of a content having a strongly disturbing effect on many readers (including reportedly O’Brien himself). The plot involves murder and a hellish and apparently circular afterlife, in which the narrator is tormented by absurd policemen in a supernatural zone called “The Parish”.

In America, two notable novels of the absurd are J.P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man (1955) and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (1961). Donleavy uses a mainly (all but infernal) Dublin setting of chaos and absurdity, largely created by the protagonist, Sebastian Dangerfield – the anglicized-hibernicized American antihero and mock-Christ figure. Catch-22 is dominated by a bureaucratic-military absurd, represented emblematically by the title, which is, of course, itself now more than a catch phrase. Set in the World War Two “theatre” of Italy, this novel was influential during the Vietnam War period, and takes on a renewed significance with the Gulf wars and the “War on Terrorism”.

As well as translating selections from the writings of Daniil Kharms (see above) and Mayakovsky’s My Discovery of America (Hesperus, 2005), Neil Cornwell is author of The Absurd in Literature (Manchester UP, 2006) and editor of Daniil Kharms and the Poetics of the Absurd (Macmillan, 1991). He is also Russian editor for the online Literary Encyclopedia. This article is the second of a three-part series.

Labels:

Absurdism,

Beckett,

Flann O’Brien,

Kafka

Tuesday, 24 March 2009

The Fox and the foxes

As I was walked up the stairs tonight, I noticed a big cat licking its paws on the top of our garden shed. "God, that cat should go on a diet," I thought, as I peered through the window. Then I realized it was a fox. "Oh well, I've got to tell my kids immediately." But when I walked through the door and made my big announcement, I got a cold reply: "Yeah, we know. There're actually two foxes in our garden. They've been there all day."

If you walk down the street where I live, in central Richmond, at say two o'clock in the morning, you can bump into one or two of these gorgeous furry fellows. I will always remember a day in January this year, when I looked out of the window and saw a fox dashing over the untrodden snow in the yellow light of the street lamps. It was an image of beauty.

But to see two foxes in broad daylight in our garden deserves some sort of celebration. So, since we have just received advance copies of our beautiful edition of D.H. Lawrence's The Fox, which William blogged about some time ago, I have decided I want to give away a few free copies to the first five lucky readers of this blog. Just send an email to "info" followed by @ and then by "oneworldclassics.com" to claim your copy. It's a great book, so hurry up!

AG

Labels:

DH Lawrence,

Foxes

Monday, 23 March 2009

The Absurd in Prose Fiction - Part I: the Roots of Absurdism

The “absurd” (see Chris Baldick’s Concise Dictionary of Literary Terms) is “a term derived from the existentialism of Albert Camus, and often applied to the modern sense of human purposelessness in a universe without meaning or value”. The “Theatre of the Absurd”, particularly Waiting for Godot, and the works of Kafka have been especially singled out. Indeed, it is largely through the Theatre of the Absurd, and Martin Esslin’s study bearing that title, that “the absurd”, as a label, achieved widespread currency through the second half of the 20th century. However, citing Kafka and Camus suggests a strong absurdist presence in prose writing as well.

Absurd theatre has its roots back in Greek drama. Approaches to the absurd can be made through philosophical texts (particularly the tenets of Existentialism, but also much earlier instances, going back as far as the Stoics, and on through “negative theology”). Later, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche are seen as significant thinkers, as, in the 20th century, are Heidegger and Wittgenstein (in particular, the latter’s “language games”). Other approaches come through theory of humour (Bergson, Freud etc.) and “nonsense”, socio-linguistic theory of pragmatics and relevance, and linguistic theory of verbal communication (particularly Roman Jakobson’s model). Lack of communication and the inadequacy of language – resulting in the unsaid, the “unsayable”, or the “unnamable” – are constant constituents, as are incongruity and incoherence. Elegiac monologue may accompany, or vie with, conspicuous pointlessness. “Mirth cannot move a soul in agony” (Biron: Love’s Labour’s Lost). Absurdist literature, however, would see that it did.

Regarding literary prose, one can indicate the proto-novels of the late classical period and, subsequently, the inventive and fantastical compositions of Rabelais as absurdist antecedents. Then, with the rise of the novel, works by Swift and Sterne come into play: satire, parody and the “English nonsense” tradition, from the 17th century to Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll – all feed into a developing absurdism. A number of prominent 19th-century writers, as proto-absurdists in their own right or as incorporators of absurd elements within more mainstream novels, also contributed to what can now be seen as a growing tradition. One thinks particularly of Gogol and Dostoevsky in Russia (the latter becoming especially important to Camus) and Dickens in England; other European influences on 20th-century absurdism include the (anonymous) The Night Watches of Bonaventura (1804) and Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror (1868).

Early in the 20th century, what we might consider proto-absurdist moments occur in works by novelists who – at first sight – seem unlikely candidates for absurdism; these include Conrad, Henry James (especially in The Sacred Fount, 1901) and Ford Madox Ford. However, it was the emergence of the modernistic avant-garde artistic movements of Futurism, Dadaism and Surrealism, along with the (at the time unknown and unpublished) Russian OBERIU grouping, that gave absurd writing such a significant boost in the period from the early 1900s to World War Two. Poetry and manifestos apart, the Italian Futurist F.T. Marinetti produced an extraordinary purported parable-novel (or “free-word book”), The Untamables in 1922; the Russian Futurists are mainly known for their poetry (though Mayakovsky also wrote plays and Khlebnikov wrote prose). Of the Dadaists, Hugo Ball and Kurt Schwitters left notable prose works. Among the Surrealists, André Breton and Louis Aragon were prose writers; not least, Breton produced an Anthology of Black Humour (1940) – a genre allegedly initiated by Swift, and a term Breton is said to have coined. Black humour surfaced too in the unlikely environment of Stalinist Leningrad, in the activities of OBERIU (the “Association of Real Art”), whose principal figure was Daniil Kharms (1905-42), active from 1927 until his suppression during the siege of Leningrad. His Kafkaesque drama Yelizaveta Bam apart, Kharms is noted for his black miniatures (sluchai or “incidents”) and for his haunting novella The Old Woman [Starukha, 1939]. A selection of his works (translated by the present writer) is collected under the overall title Incidences (Serpent’s Tail, 2006).

European prose of the inter-war years, with the general rise of modernistic experimentalism, saw abundant examples of absurdist prose. Guillaume Apollinaire wrote a number of fantastical prose works, as did his Flemish admirer, Paul van Ostaijen, who styled his satirical stories “grotesques” (see his Patriotism Inc. and Other Tales), while Joseph Roth included the absurdist novel Rebellion (1924) in a body of work chronicling the Hapsburg imperial collapse. From Central and Eastern Europe, mention should be made of Jaroslav Hašek’s The Good Soldier Švejk (1921-23), an unfinished saga of unremitting military farce in an endless march towards the front. Poland produced two slim volumes of surreal stories from Bruno Schulz (The Street of Crocodiles and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass), before he was (tragically and farcically) murdered by the Nazis. Gombrowicz’s bizarre novel Ferdydurke (1937) also deserves mention, along with certain Russian writings by Vladimir Nabokov (a Berlin resident for most of the 1920s and 30s) – especially Invitation to a Beheading.

As well as translating selections from the writings of Daniil Kharms (see above) and Mayakovsky’s My Discovery of America (Hesperus, 2005), Neil Cornwell is author of The Absurd in Literature (Manchester UP, 2006) and editor of Daniil Kharms and the Poetics of the Absurd (Macmillan, 1991). He is also Russian editor for the online Literary Encyclopedia. This article is the first of a three-part series.

Absurd theatre has its roots back in Greek drama. Approaches to the absurd can be made through philosophical texts (particularly the tenets of Existentialism, but also much earlier instances, going back as far as the Stoics, and on through “negative theology”). Later, Kierkegaard and Nietzsche are seen as significant thinkers, as, in the 20th century, are Heidegger and Wittgenstein (in particular, the latter’s “language games”). Other approaches come through theory of humour (Bergson, Freud etc.) and “nonsense”, socio-linguistic theory of pragmatics and relevance, and linguistic theory of verbal communication (particularly Roman Jakobson’s model). Lack of communication and the inadequacy of language – resulting in the unsaid, the “unsayable”, or the “unnamable” – are constant constituents, as are incongruity and incoherence. Elegiac monologue may accompany, or vie with, conspicuous pointlessness. “Mirth cannot move a soul in agony” (Biron: Love’s Labour’s Lost). Absurdist literature, however, would see that it did.

Regarding literary prose, one can indicate the proto-novels of the late classical period and, subsequently, the inventive and fantastical compositions of Rabelais as absurdist antecedents. Then, with the rise of the novel, works by Swift and Sterne come into play: satire, parody and the “English nonsense” tradition, from the 17th century to Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll – all feed into a developing absurdism. A number of prominent 19th-century writers, as proto-absurdists in their own right or as incorporators of absurd elements within more mainstream novels, also contributed to what can now be seen as a growing tradition. One thinks particularly of Gogol and Dostoevsky in Russia (the latter becoming especially important to Camus) and Dickens in England; other European influences on 20th-century absurdism include the (anonymous) The Night Watches of Bonaventura (1804) and Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror (1868).

Early in the 20th century, what we might consider proto-absurdist moments occur in works by novelists who – at first sight – seem unlikely candidates for absurdism; these include Conrad, Henry James (especially in The Sacred Fount, 1901) and Ford Madox Ford. However, it was the emergence of the modernistic avant-garde artistic movements of Futurism, Dadaism and Surrealism, along with the (at the time unknown and unpublished) Russian OBERIU grouping, that gave absurd writing such a significant boost in the period from the early 1900s to World War Two. Poetry and manifestos apart, the Italian Futurist F.T. Marinetti produced an extraordinary purported parable-novel (or “free-word book”), The Untamables in 1922; the Russian Futurists are mainly known for their poetry (though Mayakovsky also wrote plays and Khlebnikov wrote prose). Of the Dadaists, Hugo Ball and Kurt Schwitters left notable prose works. Among the Surrealists, André Breton and Louis Aragon were prose writers; not least, Breton produced an Anthology of Black Humour (1940) – a genre allegedly initiated by Swift, and a term Breton is said to have coined. Black humour surfaced too in the unlikely environment of Stalinist Leningrad, in the activities of OBERIU (the “Association of Real Art”), whose principal figure was Daniil Kharms (1905-42), active from 1927 until his suppression during the siege of Leningrad. His Kafkaesque drama Yelizaveta Bam apart, Kharms is noted for his black miniatures (sluchai or “incidents”) and for his haunting novella The Old Woman [Starukha, 1939]. A selection of his works (translated by the present writer) is collected under the overall title Incidences (Serpent’s Tail, 2006).

European prose of the inter-war years, with the general rise of modernistic experimentalism, saw abundant examples of absurdist prose. Guillaume Apollinaire wrote a number of fantastical prose works, as did his Flemish admirer, Paul van Ostaijen, who styled his satirical stories “grotesques” (see his Patriotism Inc. and Other Tales), while Joseph Roth included the absurdist novel Rebellion (1924) in a body of work chronicling the Hapsburg imperial collapse. From Central and Eastern Europe, mention should be made of Jaroslav Hašek’s The Good Soldier Švejk (1921-23), an unfinished saga of unremitting military farce in an endless march towards the front. Poland produced two slim volumes of surreal stories from Bruno Schulz (The Street of Crocodiles and Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass), before he was (tragically and farcically) murdered by the Nazis. Gombrowicz’s bizarre novel Ferdydurke (1937) also deserves mention, along with certain Russian writings by Vladimir Nabokov (a Berlin resident for most of the 1920s and 30s) – especially Invitation to a Beheading.

As well as translating selections from the writings of Daniil Kharms (see above) and Mayakovsky’s My Discovery of America (Hesperus, 2005), Neil Cornwell is author of The Absurd in Literature (Manchester UP, 2006) and editor of Daniil Kharms and the Poetics of the Absurd (Macmillan, 1991). He is also Russian editor for the online Literary Encyclopedia. This article is the first of a three-part series.

Saturday, 21 March 2009

Yasutaka Tsutsui

My last day in Japan was also the most memorable one. It was the day I met Yasutaka Tsutsui, author of three of our books – most recently Paprika, which has just been released in the UK.

Tsutsui is an author of rare quality: his works are literary, yet accessible – traditional, yet adventurous – zany, yet intelligent – humorous, yet deep. I remember when I received a submission from his translator Andrew Driver around three years ago. It was a collection of thirteen short stories – Tales from the Edge, or something like that. I was bowled over – who the heck is this guy? And I thought – just like Nick Lezard, who recently reviewed Tsutsui’s Hell in the Guardian – that he must be some thirty-something poking fun at current Japanese mores and at our celebrity-obsessed and politically hyper-correct society. I was shocked when I found out the writer was a man in his seventies, possibly more revered than Murakami in his home country. The stories, written mostly in the Seventies, turned out to be a prophetic lurch into the future – not surprising considering that a great part of Tsutsui’s long and prolific career had been devoted to the science-fiction genre.

Tales from the Edge was not a terribly sexy title to launch a new writer in this country, so I persuaded the translator to add a long novella to the collection, Salmonella Men on Planet Porno – arguably not the most powerful story in this excellent volume, but one that could attract attention and give a better idea of what Tsutsui’s fiction was about.

There are authors that you know you will like when you meet them: you have a peculiar foreboding that you would like to spend time with them and have a tea or a beer or meal together. I knew that Tsutsui would be one of those, and when he opened his beautiful house to me (and my kind interpreter Yurika) and I sat close to him, I had a feeling we had known each other for years. Conversation was easy, and we spent over one hour an a half talking about literature, his work, his new novel, the current global economical crisis and the Japanese literary scene. Surprisingly, there was no language or cultural barrier between us, and we joked and laughed as freely as if we were speaking in a common tongue.

I hope to see him again soon.

AG

Friday, 20 March 2009

Beckett

The event I visited at the Calder Bookshop yesterday, To its Beginning To its End, was first performed at the Edinburgh Festival twenty-seven years ago to critical acclaim. It was the first performance of Beckett’s work I’ve ever seen, though I read Waiting for Godot a long while ago.

It’s hard to know what to say to John Calder, who hosted the event; any of the questions I thought of suddenly seemed exceptionally banal (did you know Beckett a long time? – Yes, for nearly half a century. To which I should reply…? Was he a nice chap? What should I read apart from the famous bits? What did he like on his toast?). Actually I’d just have liked to sit down and listen to him reel off interesting and (ideally) salacious anecdotes. Bribery and corruption had already been covered earlier the same day and I was hoping for more.

But that hope was my downfall. Apart from in a few instances, I’m not sure I share Mr Calder’s taste for Beckett’s work. I read Waiting for Godot when I was sixteen and it made a strong impression on me then, but after hearing these excerpts again I realised that Beckett is really not for me.

One piece which seemed at first a culinary diatribe, Dante and the Lobster, I did like tremendously, partially because of its excellent rendering by Sean Barratt, partly because the second paragraph resonated with the day I’d just had, and because it was very funny and beautifully written. On the toasting of bread:

Of course the world has its revolting and grimy side, but Beckett seems to deliver a message of unremitting hopelessness and despair, and I can’t be doing with that on a nice spring day, free wine or no. It’s the lack of variety in that stunted outlook that gets to me, not the outlook itself.

As for absurdity, for me the climax of the evening was when one elderly fellow with a lilting accent admitted that although his attention – and even his wakefulness – had strayed quite considerably during the performance, nonetheless he had felt the pertinence of those partially incomprehensible words so acutely that – look! (an index finger here indicated a misty orb) – he had shed not a few tears over the course of the night.

It’s hard to know what to say to John Calder, who hosted the event; any of the questions I thought of suddenly seemed exceptionally banal (did you know Beckett a long time? – Yes, for nearly half a century. To which I should reply…? Was he a nice chap? What should I read apart from the famous bits? What did he like on his toast?). Actually I’d just have liked to sit down and listen to him reel off interesting and (ideally) salacious anecdotes. Bribery and corruption had already been covered earlier the same day and I was hoping for more.

But that hope was my downfall. Apart from in a few instances, I’m not sure I share Mr Calder’s taste for Beckett’s work. I read Waiting for Godot when I was sixteen and it made a strong impression on me then, but after hearing these excerpts again I realised that Beckett is really not for me.

One piece which seemed at first a culinary diatribe, Dante and the Lobster, I did like tremendously, partially because of its excellent rendering by Sean Barratt, partly because the second paragraph resonated with the day I’d just had, and because it was very funny and beautifully written. On the toasting of bread:

It was now that real skill began to be required, it was at this point that the average person began to make a hash of the entire proceedings. He laid his cheek against the soft of the bread, it was spongy and warm, alive. But he would very soon take that plush feel off it, by God but he would very quickly take that fat white look off its face. He lowered the gas a suspicion and plaqued one flabby slab plump down on the glowing fabric, but very pat and precise, so that the whole resembled the Japanese flag.Other readings, including poetry and the unwholesome First Love (a homeless man is befriended by a woman he is repelled by, uses and ignores her, gets her pregnant then walks out in disgust as the baby is born) I found uninspiring, and by the end of the performance Beckett’s consistent hatred of life was beginning to get to me… There ensued an animated conversation among the audience as to whether all this showed the absurdity of existence and reflected the world “as it is”: the falsity of progress and idealism (and hope, and optimism)… And there followed gleeful allusions to the present economic situation as though to illustrate that Beckett was more relevant than ever: just the ticket if you’ve lost your job and you're living on the street.

Of course the world has its revolting and grimy side, but Beckett seems to deliver a message of unremitting hopelessness and despair, and I can’t be doing with that on a nice spring day, free wine or no. It’s the lack of variety in that stunted outlook that gets to me, not the outlook itself.

As for absurdity, for me the climax of the evening was when one elderly fellow with a lilting accent admitted that although his attention – and even his wakefulness – had strayed quite considerably during the performance, nonetheless he had felt the pertinence of those partially incomprehensible words so acutely that – look! (an index finger here indicated a misty orb) – he had shed not a few tears over the course of the night.

Wednesday, 18 March 2009

Luigi Pulci's Morgante

Since I mentioned this work in my splenetic blog entry yesterday, I might just add that Pulci's Morgante is, in my opinion, one of the finest and most entertaining works in Italian literature. Written in the 1460s and '70s, it precedes Ariosto's Orlando furioso and even its prequel, Boiardo's Orlando innamorato (which was written after 1476). It is a swashbuckling epic of gory battles, never-ending duels, near escapes and romance – populated by preposterous knights, beautiful damsels, giants and evil spirits. Unlike many of the other chivalric poems of the time, it is incredibly funny. But what marks it as a true masterpiece is its linguistic inventiveness and the vividness of its dialogue, which doesn't follow the high-falutin example of Petrarch, but is more akin to the humble idiom used by Dante and Boccaccio. It is full of memorable lines, such as:

"E cominciava a ragionar col dente" ("And then he started thinking with his teeth")

Morgante is the name of a heathen giant who, after being converted by Orlando to Christianism, embarks with him in a series of phantasmagorical adventures. This pantagruelic character became so popular that the author was forced to use the giant's name as the title of his work. The highest point of the poem is Morgante's death when he is pinched by a puny crab. Reading Morgante in the original is a joy for any lover of the Italian language, but if you are not up to it, you can have a taste through one of the ancient or modern translations of the poem.

As you may know, Lord Byron translated the first canto of Morgante, and I consider this the best introduction to Pulci's work. After completing this translation, Byron famously informed his publisher John Murray that his greatest aspiration was to write in Italian – and he was convinced that if he was ever to write a masterpiece, that could only be written in the language of Dante, Boccaccio, Pulci and Ariosto.

AG

"E cominciava a ragionar col dente" ("And then he started thinking with his teeth")

Morgante is the name of a heathen giant who, after being converted by Orlando to Christianism, embarks with him in a series of phantasmagorical adventures. This pantagruelic character became so popular that the author was forced to use the giant's name as the title of his work. The highest point of the poem is Morgante's death when he is pinched by a puny crab. Reading Morgante in the original is a joy for any lover of the Italian language, but if you are not up to it, you can have a taste through one of the ancient or modern translations of the poem.

As you may know, Lord Byron translated the first canto of Morgante, and I consider this the best introduction to Pulci's work. After completing this translation, Byron famously informed his publisher John Murray that his greatest aspiration was to write in Italian – and he was convinced that if he was ever to write a masterpiece, that could only be written in the language of Dante, Boccaccio, Pulci and Ariosto.

AG

Tuesday, 17 March 2009

Stinker Millionaire

I know I shouldn’t even be thinking about this stuff at this time of night, let alone write about it. I know I am running the risk of transforming our anti-blog into a real blog. And I know I will probably be crucified by many film lovers and cognoscenti for this – but speak I must, or I will burst.

The thing is that flying back from Japan takes a good twelve hours. Now, you can read a book or two during that time: in fact I had taken with me volume one of Pulci’s Morgante – 680 pages of poetry and dense annotation, good enough for the round trip. But when everybody around you is watching one film after another, even if you are possessed with a will of steel you will be tempted, sooner or later, to browse the latest releases available on the small screen in front of you.

So it was that I watched one movie on my way to Tokyo, and three more movies on my way back – more movies than I would normally watch in a month. The first one, What Just Happened, was an honest Hollywood comedy with Robert De Niro, and I more or less enjoyed it, although it wasn’t one of the best in its genre. The second one, the Cohen Brothers’ Burn after Reading, was much funnier – the dialogue was a lot sharper, and although the plot gradually becomes silly and grotesque, it sort of makes sense in the end within the madcap context of the film. The third one was Doubt, with Meryl Streep and Philip Seymour Hoffman, a decent movie until its abrupt end, which leaves everything unresolved – perhaps because the director has no clue how to finish it.

Finally – and I knew full well when I pushed the OK button that I shouldn’t have chosen it – I watched Danny Boyle’s critically acclaimed and Oscar-winning Slumdog Millionaire, which the Guardian Guide describes as an “unlikely but irresistibly energetic feelgood tale with elements of Dickens, City of God and Salaam Bombay!”

Now, I have watched a few hundred films in my life, possibly even a few thousands, but I honestly do not remember having watched a worst film before. This must be worst than the worst Steven Seagal film ever shown on Channel 5 after 11:30pm. I thought it was a travesty of a movie, taking cringing to completely new heights. I felt it was false from start to finish, pretentious, pathetically acted – bad dialogue, bad story line, dodgy underlying message – a cross between a second-rate TV drama and a bad Bollywood movie. In short, everything was so awful that it made me shake with laughter.

Personally, I would have given it a Razzie, not an Oscar. If you have not watched this movie, please do try to avoid it – even if you are tempted to watch it for the decadent pleasure of seeing how bad a movie can be.

I am telling you, this film is seriously bad – not a feelgood movie, but a depressing one. Don't watch it.

AG

The thing is that flying back from Japan takes a good twelve hours. Now, you can read a book or two during that time: in fact I had taken with me volume one of Pulci’s Morgante – 680 pages of poetry and dense annotation, good enough for the round trip. But when everybody around you is watching one film after another, even if you are possessed with a will of steel you will be tempted, sooner or later, to browse the latest releases available on the small screen in front of you.

So it was that I watched one movie on my way to Tokyo, and three more movies on my way back – more movies than I would normally watch in a month. The first one, What Just Happened, was an honest Hollywood comedy with Robert De Niro, and I more or less enjoyed it, although it wasn’t one of the best in its genre. The second one, the Cohen Brothers’ Burn after Reading, was much funnier – the dialogue was a lot sharper, and although the plot gradually becomes silly and grotesque, it sort of makes sense in the end within the madcap context of the film. The third one was Doubt, with Meryl Streep and Philip Seymour Hoffman, a decent movie until its abrupt end, which leaves everything unresolved – perhaps because the director has no clue how to finish it.

Finally – and I knew full well when I pushed the OK button that I shouldn’t have chosen it – I watched Danny Boyle’s critically acclaimed and Oscar-winning Slumdog Millionaire, which the Guardian Guide describes as an “unlikely but irresistibly energetic feelgood tale with elements of Dickens, City of God and Salaam Bombay!”

Now, I have watched a few hundred films in my life, possibly even a few thousands, but I honestly do not remember having watched a worst film before. This must be worst than the worst Steven Seagal film ever shown on Channel 5 after 11:30pm. I thought it was a travesty of a movie, taking cringing to completely new heights. I felt it was false from start to finish, pretentious, pathetically acted – bad dialogue, bad story line, dodgy underlying message – a cross between a second-rate TV drama and a bad Bollywood movie. In short, everything was so awful that it made me shake with laughter.

Personally, I would have given it a Razzie, not an Oscar. If you have not watched this movie, please do try to avoid it – even if you are tempted to watch it for the decadent pleasure of seeing how bad a movie can be.

I am telling you, this film is seriously bad – not a feelgood movie, but a depressing one. Don't watch it.

AG

Monday, 16 March 2009

A Modest Proposal

I would have liked to write about the many unsung beauties of Slumdog Millionaire tonight, but something grabbed my attention on the Bookseller's website and the world will have to wait for that. This is the article in question:

Drop the rep, says Dutch

"I can only applaud this inspired recommendation by Jesse Kroger, who I am sure must have just finished reading Swift’s A Modest Proposal. But I would take her suggestion a few steps further: abolishing the reps is all very well, but why don’t we do away with bookselling altogether, and customers, and writers, and books? I can imagine a world where infinite blog writers (or maybe novel-generating computers) distribute their work free of charge on the internet or via mobile phones directly to themselves – liberated once and for all from this annoying thing, the supply chain, and that most annoying thing, people. And perhaps Google or Amazon will find a way to make money out of writers downloading or pinging their own work?

The world of books does need real people."

AG

Drop the rep, says Dutch

bookseller

I have posted a short comment, which I reproduce below. I think this world is really going bonkers, and will add no more for tonight, but go straight to bed."I can only applaud this inspired recommendation by Jesse Kroger, who I am sure must have just finished reading Swift’s A Modest Proposal. But I would take her suggestion a few steps further: abolishing the reps is all very well, but why don’t we do away with bookselling altogether, and customers, and writers, and books? I can imagine a world where infinite blog writers (or maybe novel-generating computers) distribute their work free of charge on the internet or via mobile phones directly to themselves – liberated once and for all from this annoying thing, the supply chain, and that most annoying thing, people. And perhaps Google or Amazon will find a way to make money out of writers downloading or pinging their own work?

The world of books does need real people."

AG

Saturday, 14 March 2009

Last Day in Japan – a tourist’s platitudes

After my meeting with Junichi Watanabe on Thursday, I am very much looking forward to meeting Yasutaka Tsutsui in an hour or so.

This trip to Japan has been an eye-opener in many ways. Here’s a short collection of impressions about Japan and Japanese people, or things I didn’t know before my trip. Apologies if they sound a bit trivial or clichéd.

Fat people are rare in Japan. Having said that, Japanese people like their sweets

Japanese people are, on average, better looking than Europeans and Americans

Streets have no names in Tokyo

Smoking is allowed in public places and restaurants

Food is generally excellent – and healthy

Streets, trains and buildings are super-clean. Even road works are tidy

Geishas are not prostitutes, and apparently they are not very good value for money: they entertain the rich and powerful with old-fashioned music and dances. How uncool is that?

Japanese people serve their tea very strong – at least three times stronger than the one served in UK

Coffee sucks – don’t try it. Beer is good – but expensive

Very few people speak English, and it’s tricky to find restaurants with an English menu or cab drivers understanding directions in English

A dinner in a good Japanese restaurant is around £170 per person, and it’s usually reserved for the established clientele

Every third or fourth shop front is a restaurant, and there appears to be a MacDonalds or other burger place every other block

If you walk down the street at four o’clock in the afternoon, you’ll have the impression that eighty per cent of Japan’s population is female

Italian and French restaurants are very popular in Japan. I haven’t spotted any misspellings in their names, as I sometimes do in other countries, including Britain

Cabs’ rear doors open and close automatically – easy does it

It is advisable to give cab drivers a map of where you intend to go

You can buy a pocket-sized personal computer complete with the latest Microsoft Office package for less than £150

Most books are printed on high-quality paper, including thrillers and other mass-market titles

Haruki Murakami alternates translation to writing fiction. His translations of Salinger, Carver and Raymond Chandler have become bestsellers in Japan

Female authors and male authors are at times shelved in separate sections in bookshops

My hotel TV has only one English-speaking channel: CNN. Films can be ordered on demand – including adult movies – but no pay-per-view sport channel is available

American Basketball and Baseball games are shown live on Japanese TV

Phoning from a public phone is at least ten times cheaper than in UK

Travelling on the underground is five to ten times cheaper than in London

Toilets flush hot water when you sit on them. When you flush the toilet, make sure you hit the right button or you could have your bottom wiped, washed, combed, conditioned and shaved

OK, off to meet Mr Tsutsui – will report another time, hopefully with photos too.

AG

This trip to Japan has been an eye-opener in many ways. Here’s a short collection of impressions about Japan and Japanese people, or things I didn’t know before my trip. Apologies if they sound a bit trivial or clichéd.

Fat people are rare in Japan. Having said that, Japanese people like their sweets

Japanese people are, on average, better looking than Europeans and Americans

Streets have no names in Tokyo

Smoking is allowed in public places and restaurants

Food is generally excellent – and healthy

Streets, trains and buildings are super-clean. Even road works are tidy

Geishas are not prostitutes, and apparently they are not very good value for money: they entertain the rich and powerful with old-fashioned music and dances. How uncool is that?

Japanese people serve their tea very strong – at least three times stronger than the one served in UK

Coffee sucks – don’t try it. Beer is good – but expensive

Very few people speak English, and it’s tricky to find restaurants with an English menu or cab drivers understanding directions in English

A dinner in a good Japanese restaurant is around £170 per person, and it’s usually reserved for the established clientele

Every third or fourth shop front is a restaurant, and there appears to be a MacDonalds or other burger place every other block

If you walk down the street at four o’clock in the afternoon, you’ll have the impression that eighty per cent of Japan’s population is female

Italian and French restaurants are very popular in Japan. I haven’t spotted any misspellings in their names, as I sometimes do in other countries, including Britain

Cabs’ rear doors open and close automatically – easy does it

It is advisable to give cab drivers a map of where you intend to go

You can buy a pocket-sized personal computer complete with the latest Microsoft Office package for less than £150

Most books are printed on high-quality paper, including thrillers and other mass-market titles

Haruki Murakami alternates translation to writing fiction. His translations of Salinger, Carver and Raymond Chandler have become bestsellers in Japan

Female authors and male authors are at times shelved in separate sections in bookshops

My hotel TV has only one English-speaking channel: CNN. Films can be ordered on demand – including adult movies – but no pay-per-view sport channel is available

American Basketball and Baseball games are shown live on Japanese TV

Phoning from a public phone is at least ten times cheaper than in UK

Travelling on the underground is five to ten times cheaper than in London

Toilets flush hot water when you sit on them. When you flush the toilet, make sure you hit the right button or you could have your bottom wiped, washed, combed, conditioned and shaved

OK, off to meet Mr Tsutsui – will report another time, hopefully with photos too.

AG

Friday, 13 March 2009

Go Big

While there are plenty of things to hate about America (grab a stone tablet and start chiseling) there is one that sticks deeply in my craw: the notion that everything here has to be so damn much bigger than anywhere else. Obviously we suffer short-man complex that must be compensated by owning the biggest car, house, bra, or refrigerator. Now, we give the biggest bailouts to the biggest bastards in big banking. Never has our excess been more visible and more despicable. Never has bigger been uglier. Typical American, I’m guilty myself. Several years ago I had the choice of signing with a mega publisher with a conglomerate parent company, or, a respected mid-sized press whose books I’d admired for years. Admittedly my decision to go big was only partially driven by greed and the promise of a big advance. I reasoned that the bigger house would have better, more professional resources with which to edit, design, publish, market, distribute and publicize, giving my books the best chance possible. I couldn’t have been more wrong. In the course of a five-year relationship with Big Publisher I stopped counting the number of cock-ups and failures in each vital phase of getting a book to market – in every department.