Tuesday 30 June 2009

Eye-watering News

Waterstone's parent group, HMV, has reported its full-year figures for 2008. Annual revenues for the group rose to almost £2bn – which means, obviously, a lot of DVDs, videogames and movies, and quite a few books too. Profits before tax were about £61m, i.e after giving Caesar what is Caesar's, less than 3% of total turnover. Mmm.

Waterstone's performance was even less impressive: £6m profit on a turnover of £548m (calculator, please! – that's less than 1%). Mmmmmm. A friend of mine, a stock-broker by trade, summed it up thus: "Busy fools." I take his comment was not so much – or not only – addressed to Waterstone's, but to the thousands of publishers, including us, who are oiling this wasteful machine. I am starting to see more and more the benefits of digital publishing...

Which brings me to the other chain, Borders, who announced an interesting diversification of their business, an online dating system called "Happily Ever After". If you are coming cold to this, I swear I am not joking – read the full story (and the comments) here. Another Borders news today is the launch of yet another e-book reader, the ominously named Elonex. I can see it's getting pretty busy in that market – and it looks as though there are going to be as many e-book readers' brands as there are books if we continue at this rate.

AG

Sunday 28 June 2009

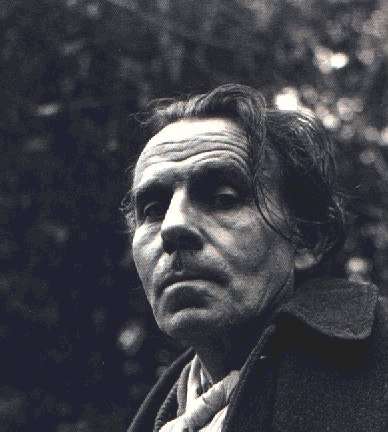

One Magazine - John Calder Blog

Just a quick post to alert you to an Edinburgh-based prize-winning magazine called One, valiantly edited by Martin Belk. As well as publishing interesting articles about literature and the arts, they have managed to secure John Calder as their Monday guest blogger – their "Man for Monday". If you want to read his latest political or literary rants, here's the link. I'll try to get John to contribute again to our blog too.

Just a quick post to alert you to an Edinburgh-based prize-winning magazine called One, valiantly edited by Martin Belk. As well as publishing interesting articles about literature and the arts, they have managed to secure John Calder as their Monday guest blogger – their "Man for Monday". If you want to read his latest political or literary rants, here's the link. I'll try to get John to contribute again to our blog too.AG

Friday 26 June 2009

Yesterday, Twitter-style

Went back home and had lunch with Elisabetta and Emiliano.

Went with them to pick up Eleonora from school, drove them to Stansted airport, dodging the traffic resulting from two car accidents.

Drove back to Richmond, worked for an hour, went to Sheen to return some videos, went back to the office, picked up William and Christian.

Drove to the station, parked the car, got on the first available train. Went to the TLS party in Knightsbridge.

Met a few friends and fellow publishers, glimpsed AC Grayling, Eric Hobsbawm and AN Wilson.

Left at 8:00, went to the Waldorf in Aldwych, picked up two friends and had dinner with them. Ate fish, drank Armagnac.

Ran across Waterloo Bridge to catch last train back to Richmond.

Caught fast train by a whisker, reached Richmond, got on first bus and arrived home before Midnight.

Checked my email, replied to a couple of messages, checked the Guardian online and found out that Michael Jackson was dead.

Read news reports on Wimbledon, read Canto VI of Aeneid in CH Sisson's translation.

Went to bed and slept eight hours – first time in many years.

You see? It's easy to do it, but I think it's also meaningless, and let's be frank: no one cares about what someone else is doing or has done. Any story, to be interesting, must to be told in a proper way, using language for what it was invented for: expression. And I firmly believe that reducing everything to a Twitter message – including classics apparently – is one of the most moronic regressions dreamt up by mankind.

AG

Thursday 25 June 2009

Barbers’ Wars

There’s this honest chap round the corner from where I live. He’s a foreigner. Let’s say he’s Swedish – although he’s not. Well, this Swede opened a tiny barber shop two or three years ago, from the back of a larger ladies-only hairdresser. This hairdresser was empty most of the time, except on Saturdays, when hords of candy-floss-haired dames descend from their dens on the hill. The Swede’s barber shop thrived: over time, he renovated it and even hired a couple more Swedish hair-stylists.

Then his lease comes up for renewal, and he realizes he's paying over the odds. He tells the hairdresser, from whom he’s renting the place, that he can get five times the square footage he’s got now for half the price just round the corner from where he is, and in a better location. So he gives the hairdresser his notice. The hairdresser goes potty, and advertises on the shop windows: MEN’S HAIRCUTS £5.00 (the Swede was charging £10.00).

The Swedish barber moves into the new place round the corner, but he still has the use of the older place until the end of the month, so he advertises MEN’S HAIRCUTS £4.00. Obviously, a lot of guys have had their hair cut at both places over the last few days.

But why did I mention this? For two reasons – the first is that this is a good time to have long hair in Richmond, and the second is that the same wars were waged between the local butchers, greengrocers and booksellers against the overpowering supermarkets over the last twenty or thirty years. Without any regulation, the result will be the same: no one will be making money, and the barber will have to close down his shop and go back to Sweden.

AG

Tuesday 23 June 2009

Publishing Law Guru

Just as a quick coda to yesterday's post, my IT guru had a peep at the referrers, and the people who have Googled "porno men" are at... number five.

"Nice," was his comment. "Depressing," was mine. That will give you a good idea as to what kind of traffic our little Alma and Oneworld Classics shop front is getting on the information highway.

AG

Monday 22 June 2009

Something to cheer about

There's nothing but bad news around us at the moment, but if there's one reason to celebrate, then this is that we are – really – under the spotlight of the whole world. How? Because we published a book called Salmonella Men on Planet Porno. Maybe for the wrong reasons (just maybe), we are getting thousands of hits every week, and this is giving us our five-minute celebrity moment in the increasingly fierce environment of the Web, where reputations are made and lost in a twitter, and where Google alerts are the measure of human brain life.

Long live the Internet then, and long live free porn for making us feel alive.

AG

Friday 19 June 2009

Sigh. . .

The big celebs for Christmas (according to this Bookseller article)

Ant & Dec Ooh! What a Lovely Pair Penguin

Sheryl Gascoigne Loving Gazza Penguin

Aled Jones Aled Jones’ Forty Favourite Hymns RH

Michael Palin Halfway to Hollywood: 1980 to 1988 Orion

Jack Dee Thanks for Nothing TW

Russell Brand My Booky Wook 2 HC

Peter Kay Saturday Night Peter RH

Harry Hill TV Burp RH

Dara O’Briain Tickling the English Penguin

Chris Evans The Autobiography HC

Simon Pegg Out of “Spaced” Hodder

Katie Price Standing Out RH

Leona Lewis Leona Hodder

Jo Brand Look Back in Hunger Headline

Ozzy Osbourne I Am Ozzy Sphere

Well, it's certainly showbizzy, full of pizzazz and chutzpah . . . and the good news is that it's going to beat the credit crunch with its glitz and glamour.

These are the times when I wish the Earth would explode like a small soap bubble.

Happy weekend.

AG

Thursday 18 June 2009

Pushkin's Eugene Onegin in Stanley Mitchell's translation - the jury is in

Adam Freudenheim of Penguin Books was kind enough to send me a copy of Eugene Onegin, one of my all-time favourites. It's one of the few Russian books I have had the pleasure to read in the original, and a book I often go back to. I have read a couple of Italian translations a few years ago, one in prose and one in verse. They were not too bad, all things considered. Of the English ones, I have read two so far – one good, one less so – and this was the third. I have only glimpsed at Nabokov's version, which some people say reads like machine translation.

Adam Freudenheim of Penguin Books was kind enough to send me a copy of Eugene Onegin, one of my all-time favourites. It's one of the few Russian books I have had the pleasure to read in the original, and a book I often go back to. I have read a couple of Italian translations a few years ago, one in prose and one in verse. They were not too bad, all things considered. Of the English ones, I have read two so far – one good, one less so – and this was the third. I have only glimpsed at Nabokov's version, which some people say reads like machine translation.I had been aware for years that Stanley Mitchell was working on a "definite" verse translation of the Onegin, as a couple of friends – one a publisher, the other a translator – tried to dissuade me from commissioning a new translation (if you follow this blog, you know I reject the idea that any translation can be definitive). So it is with great excitement and curiosity, and the highest expectations, that I started to read Mitchell's translation.

Did I like the book?

Yes, overall I did. I think I could appreciate it even in a Hungarian translation.

What did I like most?

The fact that I could read it only in two sittings – a rare thing for a lousy reader like me.

What didn’t work for me?

I don't know why but full rhymes always seem to get in the way and stick out in English. And I found myself having to reread quite a few passages, which can't be good. The narrative flow of the original is unsurpassable, of course, but the occasional inversions and archaisms – which are obviously there for the rhyme – have a very negative effect overall. The choice of reproducing Pushkin's meter was brave – but not successful, I think. Blank verse or heroic couplets could have yielded a much more natural result in English, as the iambic tetrameter is very uncommon in English poetry.

Would I publish it?

Our Oneworld Classics edition of Eugene Onegin, in Roger Clarke's translation (he has also translated Pushkin's Ruslan and Lyudmila, Boris Godunov and the Little Tragedies for us, as well as Erasmus's Praise of Folly) will appear this Autumn.

What if it came as an unsolicited manuscript?

I'd give away one of my kidneys to receive one submission of the same quality every ten years.

Did it sustain my interest throughout?

The rhyming got a bit tiresome at times. To sustain interest throughout over such a long poem you really need to be called Pushkin, Ariosto or Byron – and translators are obviously are at a great disadvantage when they are confronted with poets of such stature.

The best bit in the book?

The beginning.

The best scene in the book?

The pistol duel between Onegin and Lensky. I always like duels.

Comments on the package, editing, typesetting?

Penguin have done a good job overall, but where is the Russian text facing the translation? I also think that they could have gone for a more adventurous cover. . . Editing and typesetting was good. A few typos, but Adam had warned me and he said they have been corrected for the new reprint, so I can't be harsh about it.

My final verdict?

I don't know – I expected this translation to be something extraordinary, and I only found it to be a decent, agreeable translation, but nothing special. Not a definitive translation, then – but obviously I would like to congratulate the translator for completing such a long and difficult task. I took the liberty to send the book to one of our best verse translators, JG Nichols, and he didn't like it at all. Similarly, Roger Clarke, who had bought a copy of the Penguin edition, found Mitchell's rhymes and inversions difficult to digest. A quick look on the Internet returned this review of the Mitchell translation on the Independent, along the lines of my appraisal, although the Guardian reviewer liked it better. All in all a slight disappointment for me.

In September, I'll send a copy of our edition of Onegin to Adam, so that he can trash it on the Penguin blog . . . They say there's no bad publicity . . .

AG

Tuesday 16 June 2009

Plagiarism

But I will tell you a story which is close to home. One of our authors, Mike Croft, wrote a book called Down Deep, published by Alma in 2008, but written a few years before. This is the book's description:

"In the dead of night, a huge whale strands itself on Brighton beach. Soon whales are blocking shipping, travelling up the Thames to the heart of London, aggressively stranding themselves in incredible numbers on crowded beaches...

Amidst public hysteria, controversial marine biologist Roddy Ormond suspects the whales are communicating a terrible warning. When he tries to investigate with journalist Kate Gunning, the clues point to a scandal involving a ruthless shipping magnate and cynical government figures. Roddy and Kate are soon in grave danger. But what is the secret they must uncover? And can the code of the whales’ language be cracked? The answers are deep in the ocean, where catastrophe lies..."

You can imagine my surprise, then, when I visited Atria (an imprint of Simon & Schuster) in the States late last year and was presented The Eye of the Whale (Aug 2009) by bestselling author Douglas Carlton Abrams, in which "The unexpected appearance of a humpback whale alters a marine biologist's life, forced to race to preserve the message of its mysterious song". Reading the full description of the book on the publisher's catalogue, I was shocked by more extraordinary coincidences between the plotlines of the two books.

To think that there could have been plagiarism by either party is absurd: sometimes a coincidence is just a coincidence, especially when around half a million new titles are published every year in the English-speaking countries.

I also remember that Anthony McCarten, another of our authors, told me once that he had sent a film script about the life of Bobby Fischer to his agent, only to be told by the agent that he had just received a very similar script from another of his clients. A few years before, Anthony and co-author Steven Sinclair had launched a $230-million lawsuit against the producers of The Full Monty, which they claimed had plagiarized their internationally acclaimed play Ladies' Night (see Wikipedia article).

Nothing came of it in the end, and perhaps nothing will come of the Bloomsbury case too. I think this just goes to show that we write far too many books. And that we all wish we could become as rich as Ms Rowling by writing words on a piece of paper or a computer.

AG

Monday 15 June 2009

An apple is an apple, or In defence of (good) translation - Part Two

Can we call these operators cynical right-grabbers? Or are these publishers motivated by a sincere love of literature and by a true desire to make available books that would otherwise be hard or impossible to come by? I’ll leave it to you to decide just by browsing their “publishing” programmes (which strangely brings to mind what Google is trying to do on a much larger scale). Call me a snob, but I have always maintained that spreading bad information is worse than remaining silent.

And I want to invite you to a short trip into the past, using that much underrated time machine that is a library. Just browsing the London Library catalogue, you’ll find not one or two, but three different translations of Dante’s Banquet published between 1889 and 1909. The first was published by Kegan Paul, Trench & Co, the second one by J.M. Dent (1903), and the third one by Oxford University Press – all of them very much mainstream publishers. These volumes are printed on high-quality paper (one of them on laid paper), beautifully typeset and complete with notes. The translations are fairly accurate, and I am convinced that they rang authentic to their contemporary audience.

On the other hand, this is what on offer on our leading online retailer one hundred years after the more recent of the three translations above (Courtesy of Read Inside):

‘As the Philosopher says in the beginning of the first Philosophy, “All men naturally desire Knowledge.” The reason of which may be, that each thing, impelled by the intuition of its own nature, tends towards its perfection, hence forasmuch as Knowledge is the final perfection of our Soul, in which our ultimate happiness consists, we are all naturally subject to the desire for it.

Verily, many are deprived of this most noble perfection, by divers causes within the man and without him, which remove him from the use of Knowledge.’

Which, I would argue, is hardly intelligible by a modern reader, especially because of its haphazard punctuation and the absence of notes or any editorial context.

I don’t think the problem here lies with Dante’s proverbial obscurity. He is obviously far removed from our world and our culture, having died almost seven centuries ago. But I think the real issue is the scarcity of good translators – not necessarily motivated only by money – and good translations for our times.

AG

Sunday 14 June 2009

An apple is an apple, or In defence of (good) translation - Part One

If this is not entirely untrue for a car or TV user manual (I have translated some of those too, for my sins), when it comes to a work of literature – and especially poetry – it is a completely different matter, so it’s a bit frustrating that a large majority of readers will read a translated book and enjoy it so long as the translation is “readable” and irrespective of how old it is, how many howlers it contains and how unfaithful it is.

But if such ignorance can be excused among readers at large, I find it infuriating to find similar attitudes and preconceptions even among the bookselling and publishing community. The other day I was talking to a bookseller who more or less declared that I was a fool because I had commissioned a new translation of a popular French classic. “There’re already two other editions – I doubt any bookshop will take it on.” He may be right, and I may be heading towards loss and failure, but the “two other editions”, for the record, had been published respectively in 1959 and 1970. There was also a third edition, which was a cleaned-up reprint of a nineteenth-century translation.

Any language – and the English language probably more than many other modern languages – changes enormously year by year, let alone over a period of thirty or fifty years. It’s not just a matter of new words, but also idioms, sintax, and even grammar. So it is narrow-minded not to encourage new translations of old works, as there is no such thing as a definitive translation, and literature needs to be continually retold and readapted for the new generations.

AG

Friday 12 June 2009

Louis-Ferdinand Céline: The Imaginary – and Uncomfortable - Journey

“…notre voyage à nous est entièrement imaginaire. Voilà sa force […] tout est imaginé. C’est un roman, rien qu’une histoire fictive. Littré le dit, qui ne se trompe jamais.”

“…notre voyage à nous est entièrement imaginaire. Voilà sa force […] tout est imaginé. C’est un roman, rien qu’une histoire fictive. Littré le dit, qui ne se trompe jamais.”L.-F. Céline

Reading some articles on Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night I came across the following statement: “…important writers must not be ignored because they make us feel uncomfortable.” Anthony Burgess, a professed fan of Céline’s writings, is right: although the Journey makes us feel uncomfortable – because it certainly does, I had to take a break myself when Ferdinand Bardamu is suffering the fevers in Africa – reading it is enlightening to the extent that it agitates the very basis of our moral codes, and challenges our notions of ethics and aesthetics.

Before Sartre’s Nausea or Camus’s The Outsider, Céline explored the night of the human feelings in a post-war scenario. The term “night” refers to the hideous aspects of the human soul, its lower instincts such as envy, greed, hate or obscenity, to name only some. As far as these authors’ characters are concerned, life is a very long and unbearable night in which they have to wait until death comes to put an end to it. They all depict the sickness of solitude, desperation, absurdity, frustration and hate towards the world and its inhabitants, Bardamu probably being the worst of the lot. While at the end of Nausea Roquentin reflects that the only way of coming up with a meaning of life is by writing fiction, Bardamu cannot care less about looking for meanings, he is too convinced that there is nothing to find but death. He succeeds in almost nothing; he is a chaos of contradictions with no dreams or willingness to improve as a person. Perhaps Bardamu has a feeling of detachment closer to Camus’s Meursault, as they agree that the only way of escaping from nihilism and absurdity is death. Life is meaningless; death is certain, “one has to choose to die or to lie”. Meursault will choose to die; Bardamu, on the contrary, prefers lies. Meursault will find a sort of happiness in his silence, his self-confidence and his withdrawal from society, Bardamu instead knows how to work in society and is filled with disgust at his own. He is free to the extent that he has no bonds, but he is stuck in his own storm, the events that occur outside are just little incidents along the journey.

Céline is not interested in reproducing every action of the story in detail because, according to him, it all happens inside the character’s mind; the writing is the product of Bardamu’s hallucinatory view of what surrounds him, which is the reason why his language includes slang, popular speech and sexual and eschatological allusions. Therefore, Journey to the End of the Night is an impressionistic novel, an imaginary journey or a journey through imagination that we can certainly dislike but, nonetheless, identify with. As Paul Nizan, in his review published in L’Humanité, puts it: “Céline is not one of us… But we recognize his sinister picture of the world: he tears off all the masks and all the camouflage, he demolishes the façades of illusions and increases awareness of the degeneracy of mankind today.” Bardamu is just exposing the rotten side of human beings, all he wants to do is criticize everything he dislikes, to unveil reality, as Léon Trotsky asserts: “He only wants to tear away the prestige from everything that frightened and oppresses him.” His inability to cope with situations and to assess anything leads him to condemn all of mankind as evil. He is a real anti-hero: passive and cowardly outside; empty and confused inside.

On the other hand, a stream of dark humour flows through the novel as cynicism and sarcasm are the only defences against suffering. Bardamu is poor, he feels humiliated, ignored by post-war society, surrounded by a reality he cannot take in, and he uses humour as a rubber ring for his self-esteem. As Paolo Carile notes: “Le comique célinien apparaît ainsi comme la forme d’autodéfense d’une sensibilité humiliée et deçue, la seule forme de communication, en outre, à travers laquelle l’écrivain tente d’échapper à sa solitude…”

I would like to conclude this post by expressing my disagreement with what Clifton Fadiman said about Celiné’s art: “The art that springs out of a universal hatred may be a monstrous art, an unclassic art, an unenlightening art, but it is nonetheless art.” Is monstrous art not classic or enlightening? Are not differences and contrasts worthwhile and profound lessons?

Jessica Pujol

Thursday 11 June 2009

In Praise of Mediocrity

"NM of County Durham (9/6) asks why today there are no great artists such as Constable, Tchaikovsky, Wordsworth etc.

"Simple. In their day talent was rewarded above mediocrity, whereas today the exact opposite is true. Why would anyone dedicate a lifetime to perfecting a skill if they can get £1m for not making their bed?"

Priceless. I suppose "£1m for not making their bed" must be a reference to Big Brother or some other reality TV programme.

I don't know if it's true that talent was rewarded more in the past than it is now, but certainly the American idea that anybody can become anything – a US President, a film star, a pop singer, a celebrity, a billionaire, a footballer, an artist, a bestselling writer – has infected our way of thinking – and I'm afraid there's no going back.

AG

Wednesday 10 June 2009

Modern Art and Modern Literature

More than ten years ago I wrote in my Ars Poetastrica (lines 481–510):

Throwing the various artforms all together

gives a farrago that’s not worth the bother,

a monstrous hybrid that is false and dumb,

all sheer perplexity without a theme:

the artist’s but a road, a path, a way:

art cannot be imposed: it comes per se.

In times of decadence, like our own age,

a wild syncretism is all the rage;

and so today we see the one attempt

is to force who cares what ingredient

into art’s crucible, without a care

whether the ways are narrow, steep, obscure.

There’s talk of virtual reality,

of total art and interactivity,

of global villages and atmospherics,

of multimedia trials and hysterics.

Poor people! Names alone inspire them so

they are bewildered: why, they do not know.

Two madmen have a sort of pillow-fight,

leaping about a bed: is that a sight

made for a gallery, or a mental home?

And is this worth the least encomium:

a canvas where some doggerel is smeared

and which is all besickled and sunflowered?

This artistic decay only gets worse

with every effort that is made to press

such disparate materials into one.

At every instant a fresh blunder’s born,

and every blunder lives to aggravate

the shame of galleries of modern art.

[translation by JG Nichols – click here for the original]

Now I take a more cautious approach, and I am at least as intrigued as I am amused by Modern Art, often asking myself: "Why is it that Modern Art today tries to challenge thought and experience, whereas Modern Literature doesn't, and is content to play safe and serve the taste of the masses?" And I think about what two of our authors, Tom McCarthy and Sean Ashton, both deeply involved in the visual arts, once told me: that the real discussion of ideas has moved from the field of literature to that of art, and that most of modern fiction is not literature, but simply "production". I'm starting to believe in this more and more – for all the excesses and childishness of Modern Art.

AG

Tuesday 9 June 2009

Decadence

Ex-PFD Marcela Edwards was there, as witty and loud as ever, but tight-lipped about the PFD affair, although we were all charging on with questions.

Kirsty Dunseath of Weidenfeld / Orion complained about the size of her antipasto, which was no antipasto but a main course. Kirsty, if you want sizable food, next time please go to Soho, not the South Bank.

Carole Welch of Sceptre was there – and she told me she'll have an elbow replaced tomorrow, or something like that.

Elisabetta was there with me as my wine tank – drinking a tenth of what I gulped down and giving me a half-full glass when all the bottles were empty. Priceless virtue in a wife.

Translating couple Amanda Hopkinson and Nick Caistor were there, and as they go to bed – publishing-wise – with a lot of publishers, big and small, they were able to gossip more than most of us nine-to-five geezers about the lowlife of the UK publishing industry.

And finally cool Jorge Postigo was there, to complete our Chaucerian gathering. I haven't talked to him much, but he seemed to enjoy the place – so much so that he booked a table for five for this coming Thursday.

So all in all a good decadent publishing night. We talked about Anthony Cheetham, e-books, Andrew Wylie, the net book agreement, and a thousand other subjects that would be completely meaningless and boring to anybody sitting around us.

Good night for now.

AG

Monday 8 June 2009

Every Berlusconi has his day

Since I've been speaking Romanesco for the past few days, I thought I'd give you a Belli poem tonight:

The Life of Man

Nine months in a bog, then swaddling clothes

and sloppy kisses, rashes, big round tears,

a baby harness, baby walker, bows,

short trousers and a cap for several years,

and then begin the agonies of school,

the ABC, the pox, the six of the best,

the poo-poo in the pants, the ridicule,

the chilblains, measles, fevers on the chest;

then works arrives, the daily slog, the rent,

the fasts, the stretch inside, the government,

the hospitals, the debts to pay, the fucks...

The chaser to it all, on God's say-so,

(after summer's sun and winter's snow)

is death, and after death comes hell—life sucks.

[18th January 1833 – Translation by Mike Stocks, 2007]

You can read the original here.

AG

Wednesday 3 June 2009

Roma mon amour

Off to Rome tomorrow – or rather Genzano and the Castelli Romani – I can't wait. I haven't been for over a year, and I haven't seen my family for some time now.

Off to Rome tomorrow – or rather Genzano and the Castelli Romani – I can't wait. I haven't been for over a year, and I haven't seen my family for some time now.It looks like I'll miss Genzano's Infiorata (sigh) – which is happening the weekend after next. I haven't been to the Infiorata for ten or fifteen years – bad luck. On the other hand, on Saturday there will be a big family do at the Cacciatori restaurant. My uncle has worked there for over twenty years, and it's the restaurant at the top of Via Italo Belardi (see picture), where the Infiorata is laid out. I can assure you they'll take care of us. We'll have pappardelle al sugo di lepre and quaglie and all sorts of cacciagione. I'll just let you imagine that.

I'll have the new Penguin edition of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin with me, and I'll comment on it after my return to England on Sunday.

AG

Tuesday 2 June 2009

Death of the English Novel

"There are great writers out there," he says. "But none of them are English... English literature has lost touch with an important part of its function: to tell us who we are, where we are going and to help us understand our lives. Until a generation of writers comes along to fulfil this function, and a generation of publishers that will give them a voice, writing will remain as safe and reassuring as a suburban book club..."

What is more shocking is that if it's true more translated fiction is now available in English than, say, ten or fifteen years ago, most of it is of little literary value. There's been a general degradation of taste. We've got used to poor stuff. The parable of the English market is exemplified by Christopher Maclehose's path from the zenith of his Harvill days to his publication of the Stieg Larsson trilogy. This is not to accuse Christopher – far from it – I think he is simply a victim – like the rest of us – of the current market forces.

The market is desperate for bestsellers, not just national, but international hits. No one talks about real literature any more: only about Nielsen BookData figures. Sorry if I repeat myself (see this post or this one for more rants on this subjects), but most of the books that are now part of our canon didn't sell very well (or at all!) when they were conceived or first published. The side effect of the commercialization of writing is the stifling of true talent. Agents will only look for commercial offerings that can be easily packaged for risk-averse publishers – and this is why we have not had a great English novel in the last fifty or sixty years.

AG

Monday 1 June 2009

Mikhail Zoshchenko

The Galosh and Other Stories, by the Russian author Mikhail Zoshchenko, is one of the new acquisitions now on sale at the Calder bookshop. It is published by Angel Classics, a publishing house committed, since 1982, to introducing fine translations of foreign literature to the British public.

The Galosh and Other Stories, by the Russian author Mikhail Zoshchenko, is one of the new acquisitions now on sale at the Calder bookshop. It is published by Angel Classics, a publishing house committed, since 1982, to introducing fine translations of foreign literature to the British public.Zoshchenko was born in St Petersburg in 1894 and he became a widely celebrated writer in Russia during the Revolution and Civil War. He was known for his satirical short stories and feuilletons. But it’s about his writing, not about his life, that I would like to write, as there is already a very interesting biographical introduction by his English translator Jeremy Hicks in the Angel edition.

Zoshchenko’s writing has come as a bit of a surprise to me. When I read Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita I was pleasantly shocked, because my only exposure to Russian literature had been, so far, through Dostoevsky or Chekhov. These canonical writers are still among my favourite ones, but the notion of the devil talking to a black cat surrounded by a strongly atheistic society was not exactly what I was expecting from a Russian author. That was, as I said, a surprise, but reading Zoshchenko’s short stories I realized that there is still much more to explore and discover about twentieth-century Russian literature. If The Master and Margarita satirized the bureaucratic government in a sort of fantastic and apocalyptic way that even put into question the roots of good and evil, The Galosh and Other Stories, although still a satire of the same order, approaches it in a completely different and original fashion.

Zoshchenko abandons all pomposity and complexity – not because he was ignorant but because he wanted to find a way of communicating with the proletarian classes. His tone is simple, dry and clear: it is like a conversation, like listening to someone telling a story in a bar. At first the short stories, which are very short, might come across as simplistic and lacking profundity, but they are far from it, and despite the fact that they are written in an unpretentious language, there is a lesson – or two – to be learned in each one. The reader’s challenge lies in reading between the lines. It is not what Zoshchenko says, but what he omits that counts. These stories are little satires containing a sharp and rich criticism of the absurdity of Russian politics and its highly bureaucratic government – ranging from a bourgeois man who does not dare to leave his house for fear of being burgled and is unexpectedly trapped – and burgled – by a crafty robber who takes advantage of his greed, to a man who loses his old and ragged galosh in a tram and is very proud of living in a country in which the bureaucratic system enables him to recover it – even after endless hours of paperwork.

The Galosh and Other Stories is a literary treat. The brevity of the stories, their humour and wit, turn it into a pleasant and entertaining read that I strongly recommend to everyone.

Jessica Pujol