“…notre voyage à nous est entièrement imaginaire. Voilà sa force […] tout est imaginé. C’est un roman, rien qu’une histoire fictive. Littré le dit, qui ne se trompe jamais.”

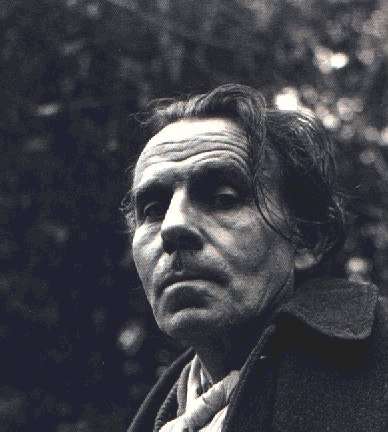

“…notre voyage à nous est entièrement imaginaire. Voilà sa force […] tout est imaginé. C’est un roman, rien qu’une histoire fictive. Littré le dit, qui ne se trompe jamais.”L.-F. Céline

Reading some articles on Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night I came across the following statement: “…important writers must not be ignored because they make us feel uncomfortable.” Anthony Burgess, a professed fan of Céline’s writings, is right: although the Journey makes us feel uncomfortable – because it certainly does, I had to take a break myself when Ferdinand Bardamu is suffering the fevers in Africa – reading it is enlightening to the extent that it agitates the very basis of our moral codes, and challenges our notions of ethics and aesthetics.

Before Sartre’s Nausea or Camus’s The Outsider, Céline explored the night of the human feelings in a post-war scenario. The term “night” refers to the hideous aspects of the human soul, its lower instincts such as envy, greed, hate or obscenity, to name only some. As far as these authors’ characters are concerned, life is a very long and unbearable night in which they have to wait until death comes to put an end to it. They all depict the sickness of solitude, desperation, absurdity, frustration and hate towards the world and its inhabitants, Bardamu probably being the worst of the lot. While at the end of Nausea Roquentin reflects that the only way of coming up with a meaning of life is by writing fiction, Bardamu cannot care less about looking for meanings, he is too convinced that there is nothing to find but death. He succeeds in almost nothing; he is a chaos of contradictions with no dreams or willingness to improve as a person. Perhaps Bardamu has a feeling of detachment closer to Camus’s Meursault, as they agree that the only way of escaping from nihilism and absurdity is death. Life is meaningless; death is certain, “one has to choose to die or to lie”. Meursault will choose to die; Bardamu, on the contrary, prefers lies. Meursault will find a sort of happiness in his silence, his self-confidence and his withdrawal from society, Bardamu instead knows how to work in society and is filled with disgust at his own. He is free to the extent that he has no bonds, but he is stuck in his own storm, the events that occur outside are just little incidents along the journey.

Céline is not interested in reproducing every action of the story in detail because, according to him, it all happens inside the character’s mind; the writing is the product of Bardamu’s hallucinatory view of what surrounds him, which is the reason why his language includes slang, popular speech and sexual and eschatological allusions. Therefore, Journey to the End of the Night is an impressionistic novel, an imaginary journey or a journey through imagination that we can certainly dislike but, nonetheless, identify with. As Paul Nizan, in his review published in L’Humanité, puts it: “Céline is not one of us… But we recognize his sinister picture of the world: he tears off all the masks and all the camouflage, he demolishes the façades of illusions and increases awareness of the degeneracy of mankind today.” Bardamu is just exposing the rotten side of human beings, all he wants to do is criticize everything he dislikes, to unveil reality, as Léon Trotsky asserts: “He only wants to tear away the prestige from everything that frightened and oppresses him.” His inability to cope with situations and to assess anything leads him to condemn all of mankind as evil. He is a real anti-hero: passive and cowardly outside; empty and confused inside.

On the other hand, a stream of dark humour flows through the novel as cynicism and sarcasm are the only defences against suffering. Bardamu is poor, he feels humiliated, ignored by post-war society, surrounded by a reality he cannot take in, and he uses humour as a rubber ring for his self-esteem. As Paolo Carile notes: “Le comique célinien apparaît ainsi comme la forme d’autodéfense d’une sensibilité humiliée et deçue, la seule forme de communication, en outre, à travers laquelle l’écrivain tente d’échapper à sa solitude…”

I would like to conclude this post by expressing my disagreement with what Clifton Fadiman said about Celiné’s art: “The art that springs out of a universal hatred may be a monstrous art, an unclassic art, an unenlightening art, but it is nonetheless art.” Is monstrous art not classic or enlightening? Are not differences and contrasts worthwhile and profound lessons?

Jessica Pujol

No comments:

Post a Comment

We welcome your comments, feel free to leave a message below.